Blueberries in Australia: Modern Farming, Pesticide Risks & Sustainable Solutions - Pest Control Port Macquarie

Blue Skimmer - Orthetrum caledonicum.

inaturalist.org

Blueberries, Pesticide Risks and Sustainable Solutions - Pest Control Port Macquarie

Australia’s love affair with blueberries has transformed the crop from a niche indulgence to a staple of breakfast bowls and smoothies. Production has exploded over the past decade, with reports showing a 240 % increase in national output during the five years to 2020‑21⁽¹⁾. Although a large share of commercial plantings is located in New South Wales, growers across multiple states have expanded plantings to meet year‑round demand⁽²⁾.

It's good to keep on-top of new regulations and news in the field, as part of working in the pest control industry in Port Macquarie. Below you will find more information about the use of OP's in Australia's agricultural sector and what is likely to be updated in legislation.

This surge in consumption, combined with protected cropping systems and substrate production, raises questions about chemical use, environmental impacts and long‑term sustainability⁽¹⁾⁽²⁾.

This article outlines the major pesticides used in Australian blueberry production, examines their risks to human health and ecosystems, and explores integrated pest management and other eco‑friendly approaches.

The chemical toolbox used in blueberry production

Blueberries are susceptible to a range of pests and pathogens, including

Queensland fruit fly⁽²⁾,

light brown apple moth⁽²⁾,

mites⁽²⁾,

thrips⁽²⁾ and fungal diseases such as

grey mould⁽²⁾ and

blueberry rust⁽²⁾.

To manage these threats growers rely on insecticides, miticides and fungicides registered by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA)⁽²⁾. The Strategic Agrichemical Review Process (SARP)⁽²⁾ for blueberries catalogues the available active ingredients and notes that their availability has been influenced by international regulatory decisions⁽²⁾. Key chemicals include:

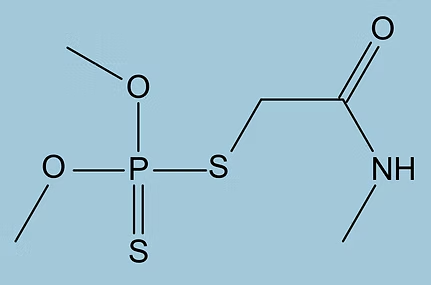

- Dimethoate⁽²⁾ – a broad‑use, systemic organophosphorus insecticide and acaricide⁽¹⁷⁾ that acts by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase⁽⁶⁾. It is registered for pre‑harvest foliar sprays and post‑harvest dips to control Queensland fruit fly in blueberries⁽²⁾. Because berry consumption has increased, the APVMA has proposed suspending dimethoate pending a safety review⁽³⁾. Dimethoate is banned in the European Union and classified by the US EPA as a possible human carcinogen⁽⁵⁾.

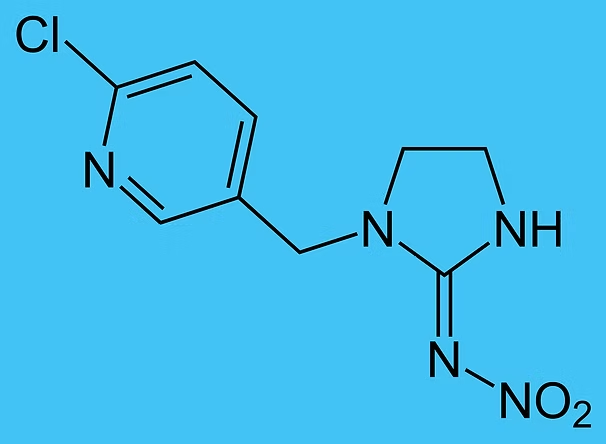

- Imidacloprid⁽²⁾ – a systemic neonicotinoid insecticide⁽²⁾ registered in blueberries for soil application to control scarab beetle larvae⁽²⁾. Field uses of imidacloprid have been removed in the European Union due to environmental concerns⁽²⁾. Reviews show that neonicotinoid residues contaminate water bodies worldwide and that these chemicals are highly toxic to many aquatic insects⁽⁷⁾.

- Spinosad and spinetoram⁽²⁾ – fermentation products belonging to the spinosyn class, registered for control of loopers⁽²⁾, light brown apple moth⁽²⁾ and thrips in blueberries under minor use permits⁽²⁾.

- Chlorantraniliprole⁽²⁾ – a diamide insecticide registered for control of light brown apple moth⁽²⁾ and fall armyworm in blueberries⁽²⁾.

- Older organophosphates and carbamates –

malathion⁽²⁾ is registered for

fruit fly control⁽²⁾,

methomyl⁽²⁾ for pests such as

Monolepta beetles⁽²⁾ and

Helicoverpa species⁽²⁾, and

trichlorfon⁽²⁾ for

mites and scale. These broad‑spectrum organophosphates and carbamates are under review due to their toxicity and persistence⁽²⁾⁽¹⁷⁾.

Chemical structure of Dimethoate by Rhododendronbusch - Own work, Public Domain.

Fungicides such as propiconazole⁽²⁾, tebuconazole⁽²⁾ and boscalid⁽²⁾ control diseases, and herbicides like glyphosate⁽²⁾ and simazine⁽²⁾ manage weeds. Propiconazole and tebuconazole residues have been detected in marine sediments downstream of horticultural catchments⁽⁹⁾, underscoring the need to use these tools within regulatory limits⁽²⁾.

How pesticide residues are regulated

Pesticide residues on blueberries are regulated via

maximum residue limits (MRLs)⁽⁴⁾. The food standards agency FSANZ defines an MRL as the highest concentration of a chemical legally permitted in a food⁽⁴⁾. The APVMA sets MRLs using residue trials and dietary exposure assessments⁽⁴⁾, and state agencies monitor compliance⁽⁴⁾.

When consumption patterns change, the APVMA can adjust MRLs or suspend registrations; this occurred with dimethoate when berry consumption doubled since 2017⁽³⁾.

Health and environmental risks of blueberry pesticides

Bee Pollinating Blueberry Flower - Active AgriScience, Why pollinators are important.

Organophosphates and carbamates

Organophosphate and carbamate insecticides, including dimethoate, malathion, methomyl and trichlorfon, act by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase⁽⁶⁾. This inhibition causes an excess of acetylcholine, leading to cholinergic toxidrome with muscarinic and nicotinic symptoms, and severe poisoning can result in respiratory failure or death⁽⁶⁾.

Chronic exposure has been linked to neurological complications⁽⁶⁾. Because these chemicals are broad‑spectrum, they kill beneficial insects and spiders that might otherwise suppress pests⁽¹⁴⁾. The APVMA’s human health assessment classifies dimethoate as a group C “possible human carcinogen” based on animal studies⁽⁵⁾.

Neonicotinoids

Neonicotinoids such as

imidacloprid⁽⁷⁾ target insect

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors⁽⁷⁾. Although marketed as safer alternatives to older chemistries, they are

systemic and persist in plant tissues, pollen and nectar⁽⁷⁾. Reviews of neonicotinoid contamination report residues in streams, rivers and lakes worldwide⁽⁷⁾.

Structure of Imidacloprid - Yikrazuul (talk) - Own work.

Laboratory tests show that some aquatic insects are highly sensitive: for example, median lethal concentrations (LC50)⁽⁷⁾ for the ostracod Cypridopsis vidua⁽⁷⁾ and the amphipod Hyalella azteca⁽⁷⁾ fall within the low micrograms per litre range, with values from 7 to 719 µg L‑¹ depending on the species and exposure duration⁽⁷⁾.

These values are orders of magnitude lower than those recorded for the standard test organism Daphnia magna⁽⁷⁾, suggesting regulatory assessments may underestimate risk.

Pesticide and nutrient runoff

Intensive horticulture often involves high inputs of fertilisers and pesticides, and heavy rainfall can wash these substances into waterways⁽⁸⁾⁽⁹⁾. Grower interviews found that blueberry farms occupy a range of topographies and soils: 43 % of growers surveyed farmed on steep slopes⁽¹⁰⁾, and only one of fourteen field‑based growers reported sandy soils⁽¹⁰⁾.

Sandy soils drain quickly and have some risk of erosion and nutrient loss⁽¹⁰⁾. The NSW irrigation manual notes that sandier soils hold less moisture than loams or clays, and that mounding and plastic mulch can reduce rainfall infiltration and increase runoff⁽¹¹⁾.

Even on heavier soils, over‑irrigation or high rainfall events can transport pesticides and nitrates to creeks and estuaries⁽⁸⁾⁽⁹⁾.

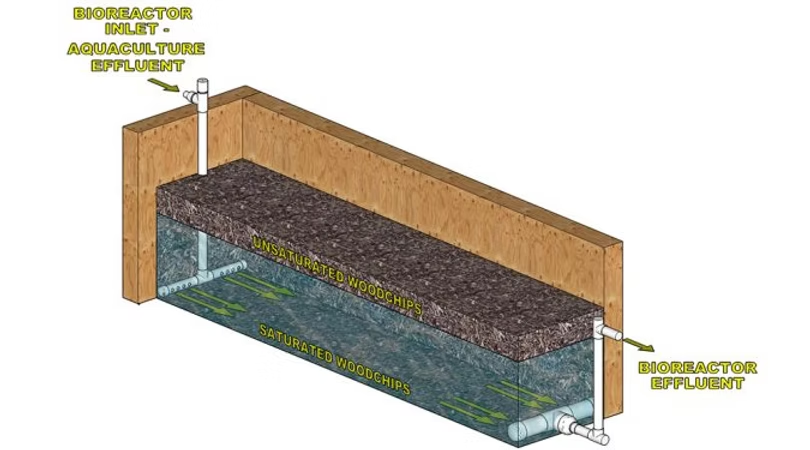

A 2024 study in Environmental Pollution⁽⁸⁾ measured pesticides in effluent flowing from greenhouses into a woodchip bioreactor. Researchers detected imidacloprid⁽⁸⁾, fipronil⁽⁸⁾ and nine fungicides⁽⁸⁾ immediately below the greenhouses; concentrations generally decreased downstream as microbial communities in the bioreactor degraded contaminants⁽⁸⁾.

In a marine sanctuary downstream of intensive horticulture⁽⁹⁾, sediment cores contained

propiconazole⁽⁹⁾ and

tebuconazole⁽⁹⁾ near the freshwater source⁽⁹⁾, and mercury and arsenic accumulation rates increased over the past century⁽⁹⁾.

These studies⁽⁸⁾⁽⁹⁾ underscore the need to manage runoff.

Occupational exposure and misuse

Safe handling practices are essential. The NSW Environment Protection Authority requires growers to undergo training⁽¹²⁾, keep spray records⁽¹²⁾ and store chemicals securely⁽¹²⁾; failure to comply can result in fines. Incorrect mixing or application can produce toxic gases and harm workers and residents⁽¹⁶⁾. A misapplication incident created a hazardous gas cloud, triggering health effects and fines⁽¹⁶⁾.

Integrated pest management and eco‑friendly alternatives

Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

IPM is a holistic approach that uses multiple strategies to keep pest populations below economic injury levels⁽¹⁴⁾. A 2020 review describes IPM as integrating preventive and curative actions while minimising synthetic pesticide use⁽¹⁴⁾.

Assassin Bug - one of many predatory insects that can control pest species.

Techniques include biological control (predators, parasites and pathogens)⁽¹⁴⁾, semiochemical lures⁽¹⁴⁾, and plant diversity through intercropping or cultivar mixing⁽²⁰⁾, along with cultural practices such as crop rotation and irrigation management⁽¹⁴⁾. Chemical control is used only when monitoring indicates pests have reached damaging levels⁽¹⁴⁾.

Predatory mites and natural enemies

Generalist predatory mites (family

Phytoseiidae)⁽¹⁵⁾ can suppress spider mites, thrips and small insects⁽¹⁵⁾. A review highlights that these mites are easy to mass rear, can survive on pollen when prey is scarce and tolerate a range of conditions⁽¹⁵⁾.

Spider mites found under the leaves of a plant - By Mokkie - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The authors advocate exploring additional mite species because current commercial strains may not suit all climates⁽¹⁵⁾. To conserve and enhance predatory mites and other beneficial insects, growers should avoid broad‑spectrum pesticides and provide pollen sources via banker plants or wildflower strips⁽¹⁴⁾⁽¹⁵⁾.

By James Niland - Flickr: Queensland Fruit Fly - Bactrocera tryoni, CC BY 2.0.

Area‑wide management of Queensland fruit fly may one day rely on releasing parasitic wasps that lay their eggs in fruit fly larvae⁽¹⁹⁾. Combining parasitoids with sterile male releases⁽²³⁾ and protein baiting⁽¹³⁾ could provide sustainable control. Such biological tools align with IPM principles by reducing reliance on organophosphates.

Habitat diversification and ecological plantings

The IPM review stresses the importance of plant diversity⁽¹⁴⁾. Intercropping blueberries with flowering herbs or planting native hedgerows provides pollen and nectar for predators and pollinators and disrupts pest movement.

Protein bait sprays and mass trapping

Protein bait sprays mix a protein attractant with a small amount of insecticide and are applied to foliage. According to the National Fruit Fly Council, these baits use minimal chemical and pose little risk to beneficial insects⁽¹³⁾. Organic baits based on spinosad provide an option for low‑input farms, and male‑lure traps can also reduce fruit fly populations and are compatible with biological control programs⁽¹³⁾.

Engineering solutions to reduce runoff

Woodchip bioreactors installed at drainage outlets can reduce pesticide and nutrient runoff⁽⁸⁾. The

Environmental Pollution study noted above found that pesticide concentrations declined as effluent passed through a bioreactor⁽⁸⁾, and microbial communities shifted towards contaminant degradation⁽⁸⁾.

Bioreactors may therefore offer a practical means to protect waterways from chemical contamination⁽⁸⁾.

A cross-section view of pilot bioreactor design. Wastewater is directed into the saturated zone towards the bottom of the trench, flowing horizontally, and providing anoxic conditions required by denitrifying bacteria. Illustration by K. Rishel, The Conservation Fund Freshwater Institute.

Protected cropping and physical barriers

Protected cropping structures – such as high tunnels, exclusion nets and mesh screens – can physically prevent insects from reaching crops and help protect berries from rain‑induced diseases⁽¹⁸⁾; they form part of an integrated, non‑chemical pest management strategy⁽¹⁸⁾.

However, insect‑proof screens placed over greenhouse vents can raise humidity and cause ventilation problems, so growers should consult a protected‑cropping designer before retrofitting or building insect‑proof tunnels⁽¹⁸⁾.

Consumer and retailer roles

Consumers influence farming practices. Choosing berries labelled as certified organic⁽²¹⁾, chemical‑free⁽¹⁴⁾ or IPM‑grown⁽¹⁴⁾ supports growers who minimise pesticide inputs. Organic production prohibits synthetic chemicals and relies on biological and cultural controls⁽²¹⁾. Washing berries before consumption and eating a varied diet reduce exposure⁽⁵⁾.

Retailers can encourage sustainability by sourcing from growers who participate in

certification programs⁽²¹⁾ and by paying premiums for low‑residue fruit. Industry apps help growers and retailers track

maximum residue limits (MRLs) and ensure compliance⁽²²⁾.

Blueberry farm in NSW.

Conclusion

Blueberry production and consumption have surged across Australia in recent years⁽¹⁾. Chemical inputs have enabled high yields but also raise concerns about human health⁽⁶⁾, pollinator decline⁽⁷⁾ and waterway contamination⁽⁸⁾⁽⁹⁾. Studies show that organophosphate insecticides inhibit acetylcholinesterase and can cause acute and chronic toxicity⁽⁶⁾, while neonicotinoids contaminate freshwater ecosystems and harm sensitive aquatic insects⁽⁷⁾.

Runoff from intensive horticulture can carry pesticides and nutrients into estuaries⁽⁸⁾⁽⁹⁾. Not all blueberry farms sit on sandy soils; however, steep slopes, mounded beds and heavy rainfall can still contribute to erosion and leaching⁽¹⁰⁾⁽¹¹⁾.

Moving towards sustainability requires a shift from reliance on broad‑spectrum chemicals to

integrated pest management. This includes biological control agents like predatory mites⁽¹⁵⁾, habitat diversification and selective pesticides, and low‑risk fruit fly baits⁽¹³⁾.

Engineering solutions such as woodchip bioreactors can reduce runoff⁽⁸⁾. By embracing science‑based practices and supporting eco‑friendly growers, Australia can continue to enjoy blueberries while protecting its environment and communities⁽¹⁴⁾.

For more information on beneficial insects check out our other blog post:

To book a free inspection:

To find out more about our approach to pest management:

References:

- Department of Primary Industries (NSW) – Blueberry Climate Vulnerability Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1499832/Climate-Vulnerability-Assessment-Factsheet-Blueberry.pdf

- Hort Innovation – Blueberry Strategic Agrichemical Review Process (SARP) (2020). Available at: https://www.horticulture.com.au/globalassets/hort-innovation/current-sarps/blueberry-sarp-2020.pdf

- Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) – Proposed suspension of dimethoate products. Available at: https://apvma.gov.au/node/11191

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) – Chemicals in food – maximum residue limits. Available at: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/chemicals/Pages/default.aspx

- ABC News – Berry consumption prompts APVMA dimethoate review. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-09-02/berry-consumption-prompts-apvma-dimethoate-review/105684394

- Robb EL, Regina AC, Baker MB. Organophosphate Toxicity. [Updated 2023 Nov 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470430/

- Sánchez‑Bayo, F. et al. – Contamination of the aquatic environment with neonicotinoids and its implication for ecosystems (Frontiers in Environmental Science, 2016). Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2016.00071/full

- Ewere, E. E. et al. – Soil microbial communities and degradation of pesticides in greenhouse effluent through a woodchip bioreactor (Environmental Pollution, 2024). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39019308/

- Taylor, M. et al. – Pesticide and methylmercury fluxes to a marine protected region of Australia influenced by agricultural expansion (Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2024). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40318260/

- Kaine, G. & Giddings, J. – Erosion control, irrigation and fertiliser management and blueberry production: grower interviews (Coffs Harbour Landcare, 2017). Available at: https://www.coffsharbourlandcare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Blueberry-grower-report-final.pdf

- Wilk, P. et al. – Irrigation and moisture monitoring in blueberries (NSW DPI, 2009). Available at: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/303325/Irrigation-and-moisture-monitoring-in-blueberries.pdf

- NSW Environment Protection Authority – Blueberry industry guidance – safe pesticide use. Available at: https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/17p4035-blueberry-industry-guidance-fact-sheet.pdf

- National Fruit Fly Council – Control methods. Available at: https://preventfruitfly.com.au/control-methods/

- Karlsson Green, K. et al. – Making sense of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in the light of evolution (Evolutionary Applications, 2020). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32908586/

- Beretta, G. M. et al. – Review: predatory soil mites as biocontrol agents of above- and below-ground plant pests (Experimental & Applied Acarology, 2022). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35939243/

- Guardian Australia – Blueberry blues: how the cash crop is causing a contamination crisis in Coffs Harbour (2022). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/sep/28/blueberry-blues-how-the-cash-crop-is-causing-a-contamination-crisis-in-coffs-harbour

- Berries Australia – Fruit Fly management without Dimethoate (Spring 2024). Available at: https://berries.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/fruit-fly-management-without-dimethoate.pdf

- Horticulture Innovation – Managing western flower thrips in production nurseries (2013). Available at: https://www.horticulture.com.au/globalassets/levy-fund-pdfs/mt09005-western-flower-thrips-nursery.pdf

- National Fruit Fly Council – Control options for Queensland fruit fly (biological control section). Available at: https://preventfruitfly.com.au/control-options/

- University of Florida IFAS Extension – Intercropping, Crop Diversity and Pest Management. Available at: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN868

- US Environmental Protection Agency – What is Organic Food?. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/organic-agriculture/what-organic-food

- Berries Australia – Berry industry mobile phone app (news article). Available at: https://berries.net.au/news/berry-industry-mobile-phone-app

- National Fruit Fly Council – Integrated pest management for Queensland fruit fly (sterile male release section). Available at:

https://preventfruitfly.com.au/area-wide-management/